Here is the abstract from a new paper on what the authors coin the ‘big problem paradox’:

Across 15 studies (N = 2,636), people who considered the prevalence of a problem (e.g., 4.2 million people drive drunk each month) inferred it caused less harm, a phenomenon we dub the big problem paradox. People believed dire problems—ranging from poverty to drunk driving—were less problematic upon learning the number of people they affect (Studies 1–2). Prevalence information caused medical experts to infer medication nonadherence was less dangerous, just as it led women to underestimate their true risk of contracting cancer. The big problem paradox results from an optimistic view of the world. When people believe the world is good, they assume widespread problems have been addressed and, thus, cause less harm (Studies 3–4). The big problem paradox has key implications for motivation and helping behavior (Studies 5–6). Learning the prevalence of medical conditions (i.e., chest pain, suicidal ideation) led people to think a symptomatic individual was less sick and, as a result, to help less—in violation of clinical guidelines. The finding that scale warps judgments and de-motivates action is of particular relevance in the globalized 21st century.

My first thought was that 15 studies is a lot, and while 2,636 is not a huge sample size for a single study, it becomes even less promising when divided across 15 studies (i.e., an average sample size of ~175). For that reason alone, I decided to take a closer look at the studies in the paper. The first thing I noticed was that a lot of the studies were preregistered, and that surprised me. How can so many results be in line with the preregistration when the samples are rather small?

Now that I have looked into the preregistrations of the paper, what stands out to me is not the ‘big problem paradox’ itself, but the construction of the paper. In brief, the issue is that – with the available information – I am not convinced about transparency of the study despite almost all of the studies being preregistered.

Most of these studies have a very small sample size (with studies having N less than 100) and show large effects (with a few of the studies showing a Cohen’s d greater than 1). I do find it very impressive – even if all of these effects are true effects – that there is not a single false positive or false negative across 15 studies with such small sample sizes (and that the smallest effect is a Cohen’s d of 0.30).

The authors are explicit about only expecting medium to large effects, which is all they find. Why do they expect that? Here is the relevant paragraph in the paper: “We report a series of studies that test for the big problem paradox, its underlying process, and implications. Across experiments, to maximize power, we targeted a minimum sample of 50 participants per cell. Based on pilots, we anticipated medium to large effects.” This raises concerns about transparency and consistency. Pilots, in plural? How were these pilot studies conducted? What was the objective? Are these pilot studies described anywhere? Was it decided in advance that these pilots should not be reported in the final manuscript?

I bring it up here as more or less all studies are preregistered, and all data is available here. The problem is that there is no way of knowing whether these preregistrations are all the preregistrations being made in relation to this study, and I have good reasons to believe that several steps were taken to decide what studies should be included and in what order. This is a very basic problem with the timeline of the paper, i.e., that it is not possible to fully evaluate the sequence of events and decisions.

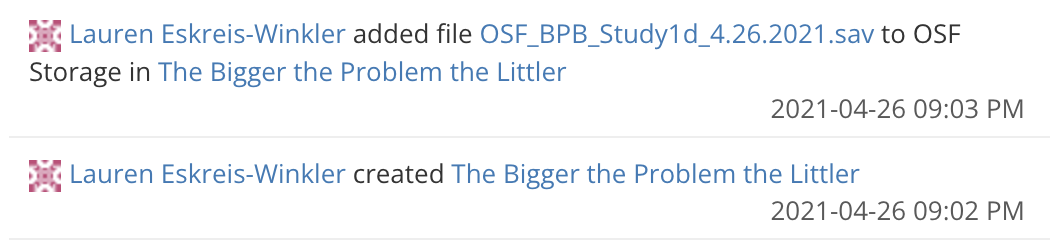

The OSF page with all the replication material was created on April 26, 2021. The same day an SPSS file named OSF_BPB_Study1d_4.26.2021.sav was added to the page. Interestingly, there is no mention of Study 1d in the final paper (nor any data with the time stamp 4.26.2021). And here is a fun fact: The first study reported in the paper, Study 1a, was preregistered on August 30, 2023 (more than two years after the data to Study 1d was added).

Alas, it is currently impossible to access older versions of these files. The OSF is not as good as GitHub in keeping the actual files. That is, when a researcher changes or deletes a file, there is no way to access these old files. So if I click on the link to OSF_BPB_Study1d_4.26.2021.sav, it does not return any version of the file.

Next, certain unusual patterns begin to emerge in files changing names over time.

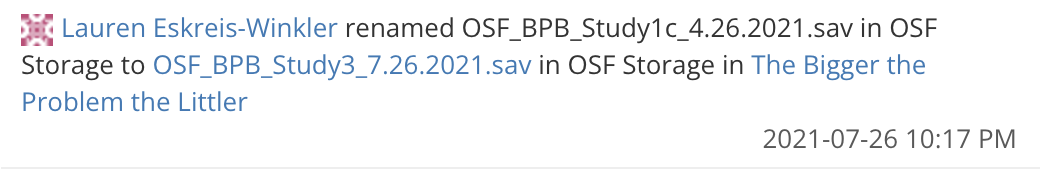

For example, an SPSS file originally labeled for Study 1c was later relabeled as Study 3 (another study will be Study 1c later, I guess).

One minute later, Study 2 was relabeled as Study 5.

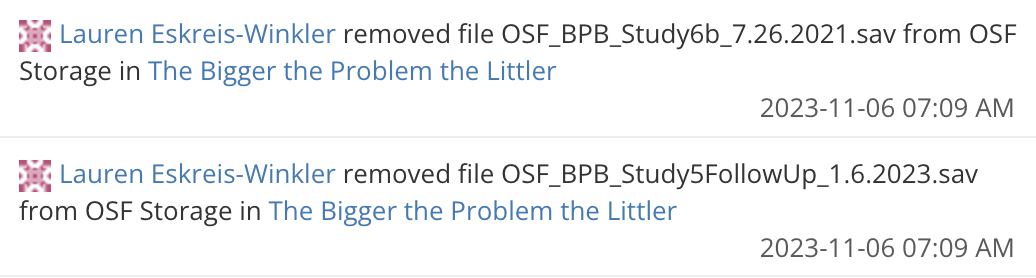

I should note that this is not inherently problematic. It is completely normal within psychological research to change the order of the studies to improve the structure or the flow of the evidence (often, but not always, at the request of reviewers). However, what I am not sure is normal is to remove data from a paper. Here is one example from November 6, 2023, several months before the paper is being submitted to a journal, where two datasets are removed.

The same date some other datasets were added to the page, but Study 6b was not one of them. Actually, there is not even a Study 6b in the published paper. My theory is that there was not even a Study 6 in the first submission of the paper to the journal. If you look at the preregistration of Study 6, you can see that it was preregistered after the submission of the article to the journal. The paper was received by the journal on February 15, 2024, and revisions were received on June 18, 2024 (the paper was accepted the same day). I can only interpret this in a way that Study 6 was only conducted as part of the review process (most likely as part of an R&R).

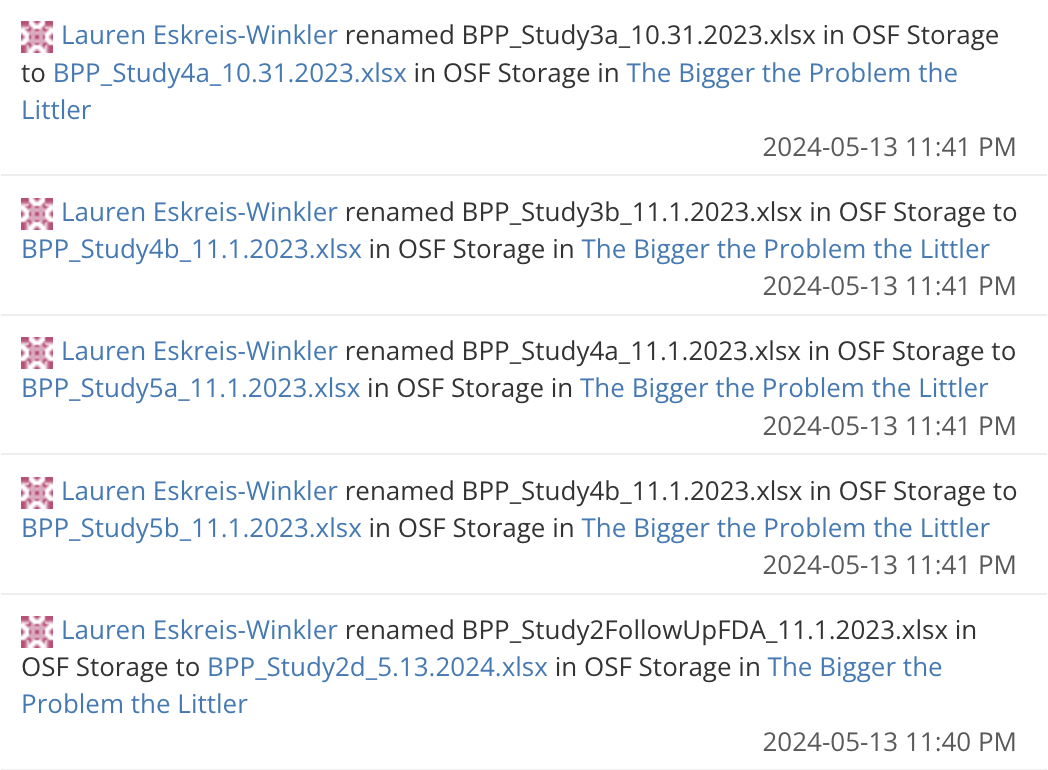

Around the same time, you also see that studies got renamed to change the order of the studies in the paper. In the example below you see all studies in Study 3 now being for Study 4, the studies in Study 4 being Study 5, and Study 2 follow-up is now Study 2d (not to be confused with Study 2 follow-up in the final paper).

When I looked into the other preregistrations as well as the data, I noticed several similarities and some reasons to be concerned (the preregistrations not already mentioned above are Study 1b from September 15, 2023, Study 1c from August 3, 2023, Study 2b from January 22, 2021, Study 2c from May 2, 2024, Study 2d from November 1, 2023, Study 2 follow-up from November 1, 2023, Study 3a from May 9, 2024, Study 3b from May 10, 2024, Study 4a from January 5, 2023, Study 4b from July 31, 2023, Study 5a from January 27, 2021, and Study 5b from January 27, 2021).

First, all of these studies have very small sample sizes and no justifications are provided throughout the preregistrations on how the sample size would be decided. When a study is conducted on Prolific, why limit the sample to 100? With all of these small studies, it is surprising that not a single one of them reports a Cohen’s d smaller than 0.3.

Second, the data for a lot of these studies is collected on the same day as the preregistration. The preregistrations are generally sparse in terms of information and with no information about what paper they will be used for or what the specific predictions are. In one of the preregistrations it says “We test whether people think a problem is less severe when they learn about its prevalence.” with no information about the hypothesis.

Third, the studies were conducted over multiple years with some of the studies being preregistered even before the OSF page was created and others after the paper was submitted for review. This is not inherently problematic, as research projects can take years to complete. However, for studies with such small sample sizes, where data collection takes less than a day, the lack of detailed preregistration information seems strange.

Fourth, the preregistrations are available on different platforms and none of them are linked to the project. If you go to the registrations of the project, it just says “There have been no completed registrations of this project”. Some of the preregistrations are available on AsPredicted, and others on OSF.

The large effect sizes (all statistically significant), small sample sizes, deleted datasets from OSF, preregistrations scattered across two platforms, and the lack of a coherent overview of preregistrations (and data collection) all raise concerns about the reliability of the conclusions.

We should – as always – not put too much faith in preregistrations and, instead, consider the paper the preregistration of the replication.