Is it possible to have news without any biases? I doubt it. While it is technically possible to have ‘unbiased news’, it is not desirable nor reflective of how most journalists work. On the contrary, I will argue that bias is a principal part of any news coverage. I believe a concept such as ‘biased news’ is an oxymoron. What people often mean when they talk about biased news is that the news is biased according to principles that are not in line with journalistic principles and, accordingly, the biases that they should be shaped by.

In brief, if news is unbiased, they would be a random sample of ‘events’ taking place in the world. Again, while technically possible, I would argue that this is not ‘news’ but ‘data’. Accordingly, news cannot be a random sample of information, hence the need for a bias. When we do talk about biased news, we do not talk about a bias compared to an objective baseline of ‘unbiased news’, but a bias relative to another bias. To understand news, we have to understand selection biases.

There are at least two distinct ways in which a selection bias come into play in the news: in the selection of events and the selection of features of the events. However, we cannot understand news by looking at these two selection biases in isolation as considerations about both shape the news coverage.

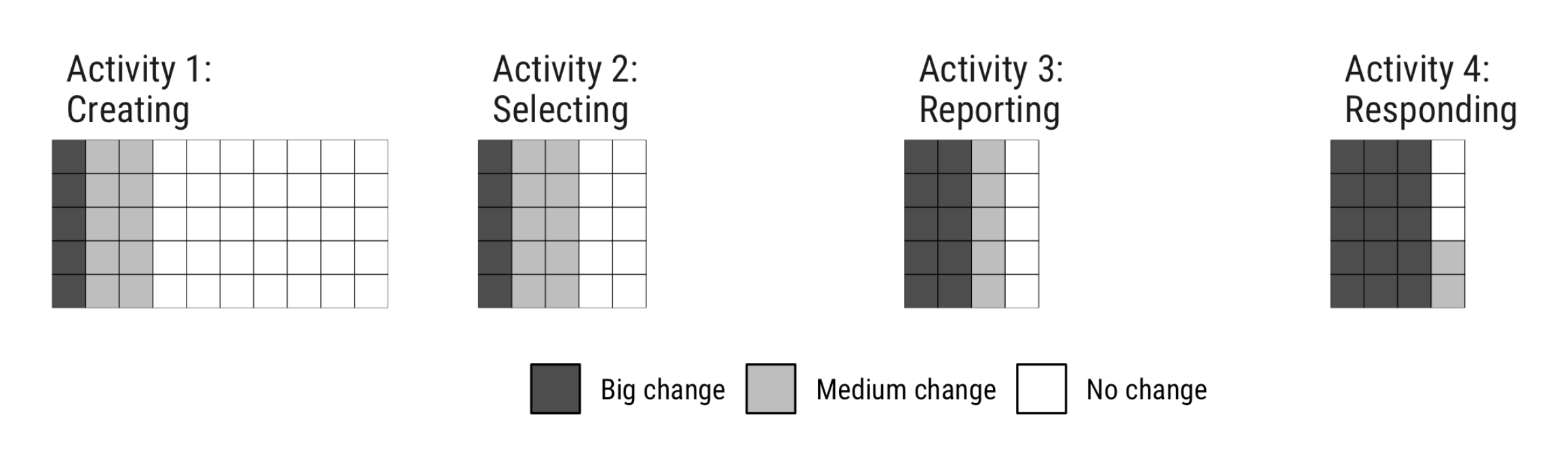

This might sound abstract, if for no other reason than it is abstract. In my work with Zoltán Fazekas on opinion polls, we devoted a lot of time discussing everything from ‘what is news?’ to ‘what are the relevant comparisons journalists can make when they want to evaluate changes in opinion polls?’. In our book we developed a framework to understand and discuss some of these dynamics. Here is Figure 2.3 from the book:

What we show in our book is that opinion polls (as ‘events’) are not covered in an unbiased manner in the news. On the contrary, opinion polls travel through different stages that all ‘bias’ the news. Of particular relevance here is activity 2 (Selecting) and activity 3 (Reporting) in the figure. Here, we show how opinion polls showing greater changes are more likely to be selected for reporting and, once selected, such changes are more likely to be framed in terms of change in the news coverage (even when all changes in an opinion poll are within the margin of error).

However, I believe that such selection biases are relevant for most, if not all, news. That is, our work is not only useful to understand the media coverage of opinion polls. The amazing feature about opinion polls is that we can quantify, measure and estimate the magnitude of specific biases related to change. The point I want to make here is that even when we are not looking at numbers in opinion polls, we can understand news as a ‘selection bias’. The selection bias is about the criteria journalists apply when they select and report specific events.

Journalists do not always agree on what are the crucial ‘event properties’ when deciding whether something is newsworthy or not (see, e.g., Strömbäck et al. 2012). However, the important aspect here is that they do not simply select events at random, and once an event is selected, select features about an event at random. For example, even if an opinion poll is found newsworthy, the features of the opinion poll that will be reported are not selected at random.

To my knowledge, several studies demonstrate similar dynamics on how events are selected and reported in the news. A few studies, for example, have looked at the news coverage of parties and politicians. Kostadinova (2017) shows that not all party pledges end up in the news, and there are systematic differences in what ends up in the news. Meyer et al. (2020) demonstrate how party messages are more likely to make it into the news if they are already important to the media or other parties. Greene and Lühiste (2018) show how gender characteristics of prominent party members shape whether and how policy messages are covered.

In relation to the media coverage of the economy, Soroka (2012) examines how unemployment numbers are turned into news in the United States. This is another great example of how we can examine how the distribution of information in the media differ from the unmediated distribution of information. Again, a key finding here is that it is by no means random what economic figures end up in the media coverage.

Several studies, primarily within the field of sociology, have also looked at what protests and demonstrations make it into the news coverage. McCarthy et al. (1996) compared police records of demonstrations in Washington, D.C. with the media coverage of demonstrations. They found that the size of a protest and its relevance for the current media cycle were the best predictors of coverage. Oliver and Myers (1999) looked at 382 in police records and found that local newspapers covered 32% of the events, with a preference to events that, for example, involved conflict. Myers and Caniglia (2004) examined differences in the news reporting of civil disorders in the late 60s to examine differences in what events made it into the news.

In sum, there is no reason to believe that ‘events’ are selected at random in the news coverage, nor that the features related to the events are being picked at random. However, this is not a problem per se. Good news is not about covering random events, but being explicit about the methodology used to ‘sample’ events and the relevant features of the events.

With that in mind, let us consider a concept such as ‘political bias’ in the news coverage. There are two different ways to think about a political bias. First, it might be that the media has a preference for political content over non-political content. Second, it might be that the media has a preference for content in line with a specific political view (e.g., a preference for right-wing or left-wing content). To understand some of the complexities, we can see a political bias both in the selection of events and how such events are being reported.

If we take a political scandal with a right-wing politician, for example, there are many ways in which a bias can come into play. A media outlet has to decide whether it would like to report on the event or not. If not, then it should decide whether it would like to report on non-political content or another political story. If the story is selected for reporting, there are many ways to report such an event. It might even be that the coverage will be about how the political scandal is a non-event, i.e., not even a newsworthy story. Accordingly, studying political biases in the media is a complicated matter.

To make matters even more complicated, while we talk about the selection and reporting of events, notice how there are also two other activities in the figure above. Whether an event is ‘created’ in the first place (e.g., whether a political scandal exists as an event), can be conditional upon what is considered news in the first place. A political scandal might only be an ‘event’ once it is found newsworthy. Furthermore, journalists do not simply report the news without taking demand characteristics into account, i.e., what the audience is interested in reading about.

To understand news, we need to think about ‘selection biases’ and how such biases come into play (and why). And not only a selection bias in terms of what events are deemed fit to print, but also a selection bias in the characteristics of an event that are being covered (and how).