In a study titled ‘We Made History: Citizens of 35 Countries Overestimate Their Nation’s Role in World History’, the authors conclude that most people overestimate the contribution of the country they are currently living in to world history. This is, according to the authors, evidence of national narcissism.

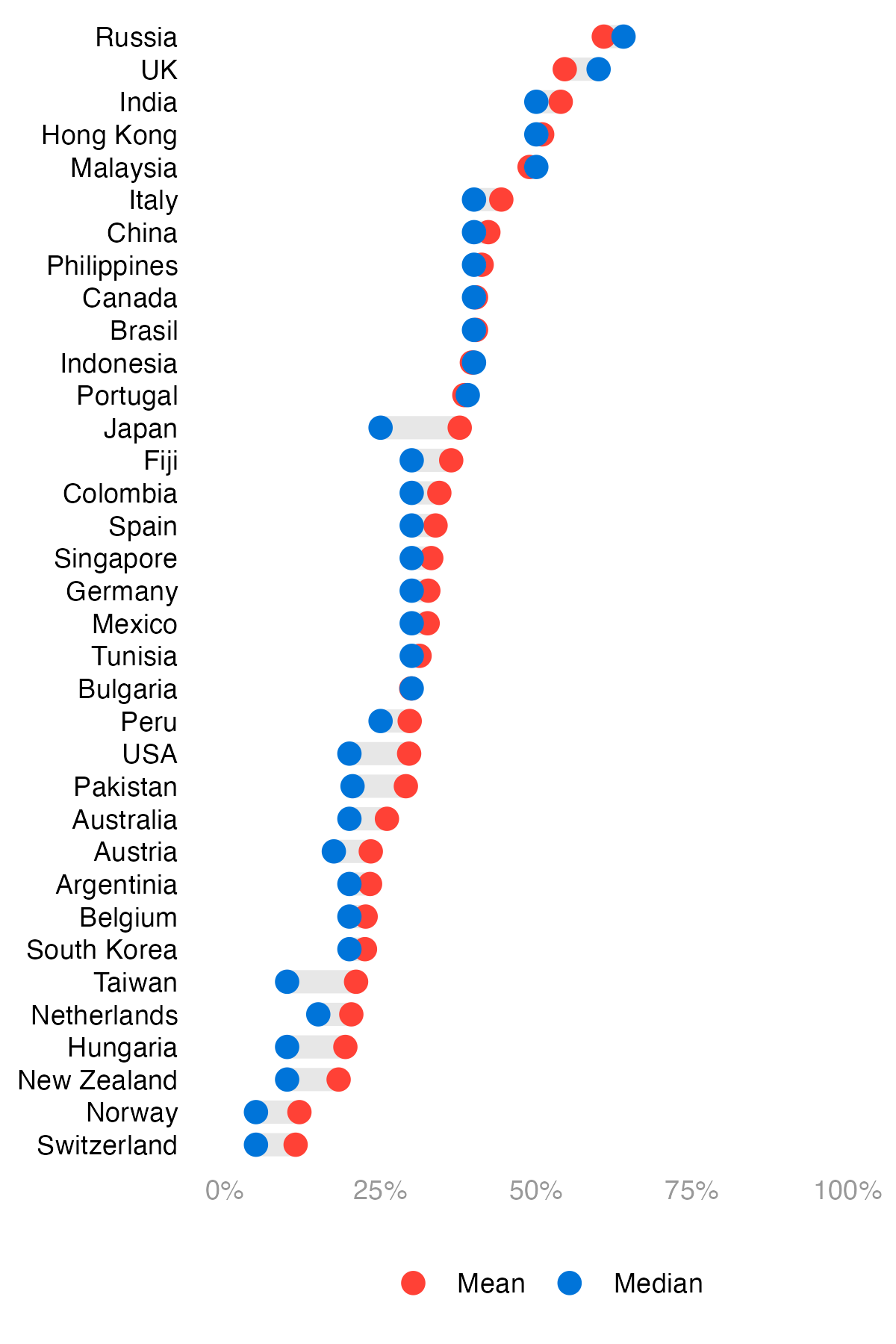

The authors asked students in 35 countries to answer the following question: “What contribution do you think the country you are living in has made to world history?” The respondents could then provide a percentage answer, i.e., from 0% to 100%. 0% will mean that the country made no contribution to world history at all, I guess. When adding up the country averages, the authors find that the total estimate was 1156%. The figure below shows the mean and median estimate for each country.

I have a few specific concerns with these numbers and, in particular, what we can conclude on the basis of such findings (besides concerns related to the obvious challenges related to student samples). First, again, the authors say that the findings are evidence for national narcissism, but I am not convinced that the measure used here is a better measure of national narcissism than alternative survey measures in the literature (see, e.g., Cichocka et al. 2023 for a recent example). Instead, it is just as likely that there are more simple psychological explanations for the data (see, e.g., Landy et al. 2018 on the psychological processes involved in proportion estimation in surveys). If this is indeed a measure of national narcissism, I would like to see some sort of validation.

Second, how can we be sure that respondents even understand the question? Might it be that respondents do not think about the question as a proportion estimate, i.e., a question where estimates for all countries should add up to 100%? That is, if asked for all other countries in (world) history as well, would the respondent end up with a sum of 100%? Noteworthy, the authors are explicit about potential issues with how the respondents might interpret the question:

The question was deliberately vague, so subjects may have interpreted it as referring to “since my country became an independent entity with this name” or “peoples of the land that is now my country throughout all time.” It is also unclear how students understood what counts as a contribution to world history.”

And how can we be sure that students in different countries interpret such a question in a similar manner? In other words, while it might be unclear how students understand what counts as a contribution to world history, such understandings might not be identical across countries, making it even more of a flawed measure of national narcissism. Again, some validation is needed.

Third, and related, there is no missing data in the actual dataset. In other words, all respondents provided an answer to the question. It is unclear whether this is because respondents with missing data are excluded from the dataset, or whether they were forced to give a response. When I looked at the wording of the specific question in the survey, I can see that it was not an option for the respondents to say don’t know. When forced to provide a number between 0 and 100, we should be concerned about the quality of the data. In other words, we would have much better data if the respondents were allowed to say don’t know to the question if they had no idea about what to say.

Fourth, such a question would work better if there was an objective baseline. If we have no way of comparing the answers to how much a country actually contributed to world history, we cannot really say whether a national average is evidence for national narcissism or not. In the figure above, you can see that the three countries with the greatest averages are Russia, UK, and India. As these three countries have most likely contributed more to world history than, say, New Zealand, Norway, and Switzerland, how much greater should these averages be before they are evidence of national narcissism?

In general, I am not in favour of asking respondents to provide percentage estimates in surveys. The main reason is that people are not good at thinking in percentages, especially when the question is vague and there is no objective baseline to rely on when we want to evaluate the accuracy of the individual as well as aggregated answers. While it is great to see alternative measures of national narcissism, I would not recommend using this particular measure in cross-cultural research if you are interested in understanding national narcissism.