Here is a list of issues, challenges, and problems with nudging. It is by no means an exhaustive list, nor am I sure whether I agree with all arguments presented below. I try to make as strong a case against nudging as I can, but this is not the same as my case is strong, or even convincing. The purpose is not to reject nudging as a concept, theory, method or/and research agenda, but to stipulate a discussion (or multiple discussions) on the merits of nudging.

The ten issues are:

- No clear definition

- Unintended negative effects

- No cumulative science

- No clear comparison

- No effect on big problems

- Focus on individual solutions

- Bias towards biases

- Nudging as a non-intervention tool

- Buzzword for business

- Ethical concerns

Below, I briefly outline each of the issues. Some of the challenges I outline are interlinked and they should not necessarily be seen as equally important, or even ranked by their relative importance. Again, do see them as a proposal for a constructive discussion rather than my attempt to put a popular concept six feet under.

1. No clear definition

Nudging is a popular concept. Interestingly, it is popular despite a clear definition rather than because of it. The challenge is that most interventions and features of the environment can count as nudges nowadays. Consider the definition of a nudge in a recent article by Cass Sunstein (2022): “A reminder is a nudge; so is a warning. A GPS nudges; a default rule nudges. Some nudges are educative; consider labels and warnings. Other nudges are architectural; consider automatic enrollment or website design that places certain options first or in large font. To qualify as a nudge, an intervention must not impose significant material incentives. A subsidy is not a nudge; a tax is not a nudge; a fine or a jail sentence is not a nudge. To count as such, a nudge must fully preserve freedom of choice. If an intervention imposes significant material costs on choosers, it might of course be justified, but it is not a nudge.”

The problem is that it is now easier to identify a nudge by what it is not. A nudge is an intervention that is not imposing material incentives. Or, more specifically, not imposing significant material incentives. In other words, there are too many interventions that can be a nudge and it might be easier, at this point, to simply say “I know it when I see it” than trying to provide a satisfactory definition of nudging.

To make matters worse, whether something is a nudge or not is conditional upon whether it is in fact nudging people. That is, we cannot necessarily conclude a priori whether an intervention is a nudge or not. To understand this, we need to look at the original definition of a nudge provided by Thaler and Sunstein in their book, Nudge: “A nudge […] is any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives.” (emphasis mine)

To illustrate the problem, the statement that a “reminder is a nudge” is not technically true, unless the reminder actually nudges people (i.e., alters people’s behavior). Furthermore, a reminder might work only for some people, so whether an intervention is a nudge or not depends upon the composition of the people we nudge (or try to nudge). For example, whether something is imposing significant material incentives depends upon background characteristics of the people in the study. What will impose significant material incentives on me will most likely impose insignificant material incentives on Bill Gates. What is a nudge for me might not be a nudge for you.

In 2021, I wrote a post on why this particular definition is problematic. In brief, we will always conclude that a nudge is working (if not, it is not a nudge), and researchers, politicians and the public alike will misunderstand how effective nudging is as a policy tool. That is, only when an intervention alters people’s behavior, it can get the ‘nudge’ label (i.e., a survivorship bias in what interventions that can be seen as nudges). If not, it is a non-nudge, whatever that is (which is not necessarily an intervention imposing ‘significant material costs on choosers’).

To further illustrate how everything can be nudges, consider the following description from Cass Sunstein’s book, How Change Happens:

Nudges are choice-preserving interventions, informed by behavioral science, that can greatly affect people’s choices. There is nothing new about nudging. In Genesis, God nudged: “You may freely eat of every tree of the garden; but of the tree of knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it, you shall die.” The serpent was a nudger as well: “God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.” With a threat and a promise, and distinctive framing, God and the serpent preserved freedom of choice.

I guess God is in every nudge and the devil is in the detail. Noteworthy, I don’t believe it is problematic to have a definition that can capture multiple different ideas, and in several cases it can even be beneficial, but if it is easier to define what something is not, it is only fair to discuss the actual merits of the concept.

For more on these issues related to the definition of nudging, and in particular the methodological implications for how we think about effect sizes and meta-analyses, check out my previous posts here, here, here and here.

2. Unintended negative effects

The world is a muddy place and our theoretical expectations do not always align with empirical evidence. Unsurprisingly, issues related to the definition aside, it turns out that nudges do not always work as intended, if at all. Nudges can have effects that are indistinguishable from zero, and, maybe even negative effects.

What do we call a nudge with unintended effects? That is, what is a nudge that is nudging people, but not in the predicted direction? Keep in mind that a nudge is “any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives.” Is it still a nudge if the impact is in the opposite direction?

By definition, we always expect a nudge to improve an outcome, but it can also worsen it. In other words, nudges can have unintended/backfire/reverse/opposite effects. One recent example is a paper by Kalil et al. (2023) on how reminder messages have unintended effects on the quality of the task in the study. As the authors conclude: “This demonstrates that nudging might have the unintended consequence of reducing the quality of the task (reading).” But, again, is it a nudge in the first place if the intervention is not… nudging people? Another recent example I am familiar with is a study on traffic safety messages by Hall and Madsen (2022), that concludes: “Contrary to policy-makers’ expectations, we found that displaying fatality messages increases the number of traffic crashes.” (However, see the discussion by Jason Collins on this particular study.)

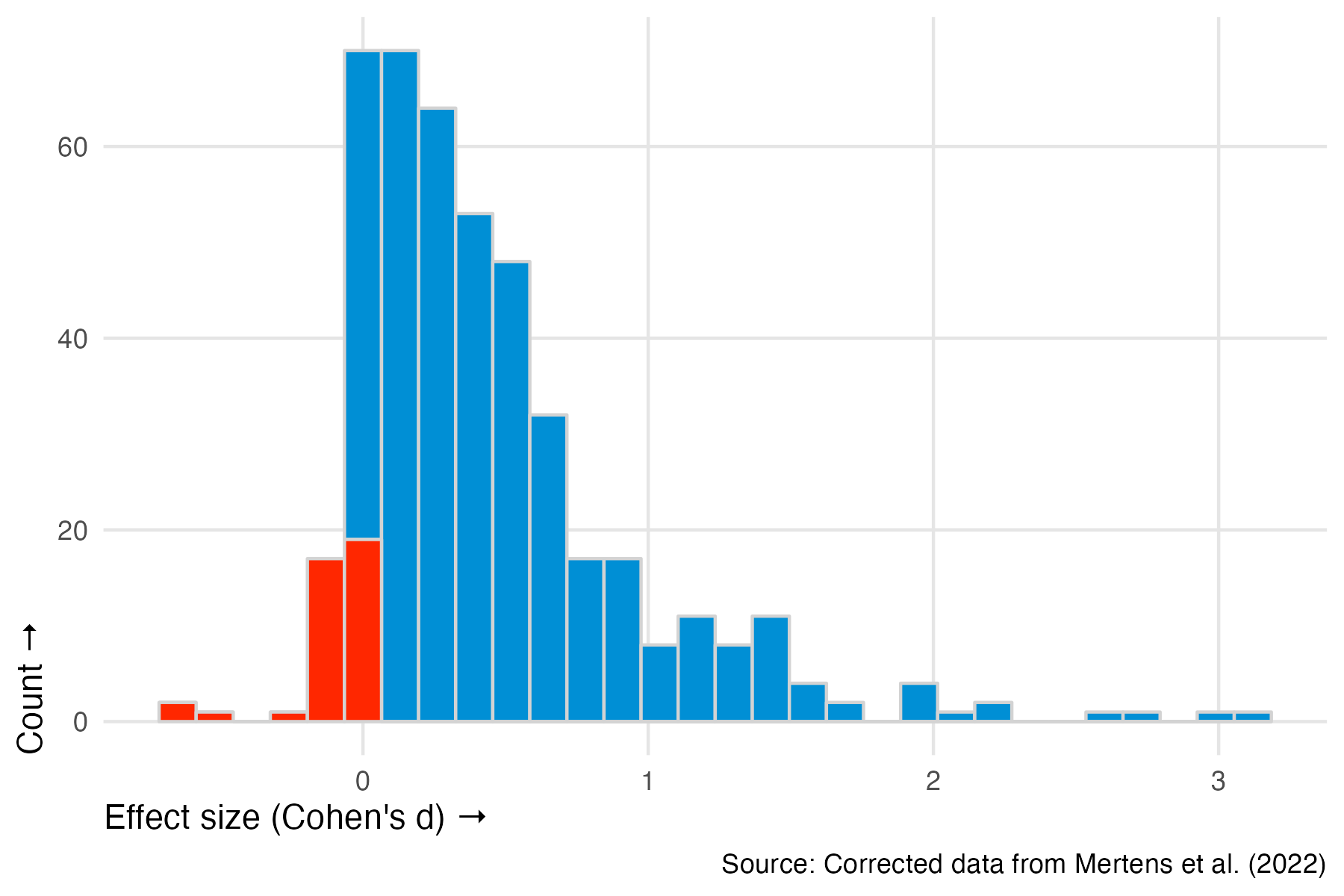

In the figure below, we can see that effect sizes in studies on nudges are not always positive (i.e., in the expected direction). The data is from the meta-analysis by Mertens et al. (2022). 40 out of 447 effects – almost one in ten – are negative (i.e., in the unintended direction). Of course, most of them are not statistically significant, and in several cases they have low statistical power, but we should at least consider what concept(s) we use in our theories and how useful they are in the face of unexpected, unintended effects.

This is by no means a new concern. There are several old cases out there on how nudges do not always have the intended effects. For example, take a look at this article from 2010 in Slate, titled ‘Nudges Gone Wrong’, on how a program designed to reduce energy consumption made some people consume more. Or this article from 2011 in the Wall Street Journal on how retirement-saving defaults can have the opposite effect for some people.

Despite the fact that we have known of such dynamics for more than a decade, we are no better equipped today to deal with such challenges theoretically. My argument is that it is partially due to how we define, conceptualise and understand nudges and the inherent inability to consider how and when nudges go wrong.

In sum, the concept of nudging is biased towards positive findings (both in statistical terms and theoretical terms). That is, we are not only more likely to define nudges according to whether they work, we are also more likely to end up with nudges that work because we do not pay sufficient and systematic attention to “nudge failures”.

3. No cumulative science

Nudging has been around for a long time but how much do we actually know today compared to, say, five years ago? My guess is not a lot. If anything, what we know today is that what we used to believe was true about nudging five years ago is no longer true (consider the work of high-profile academics such as Brian Wansink, Dan Ariely, and Francesca Gino). We know that a lot of studies do not replicate, which is definitely some sort of improvement. However, as a body of knowledge, are we left with more than a house of cards? More specifically, we have a deck of cards – a ‘confirmation bias’ card, a ‘framing effect’ card, an ‘anchoring bias’ card, etc. – but when we add it all together and talk about nudging as a research agenda, what exactly are the prospects for a cumulative science?

While there are overviews of nudging techniques and frameworks (e.g., MINDSPACE), there is no overarching theoretical framework that can guide us towards scientific progress in the domain of nudging. Combined with the challenges mentioned above, in particular the issue with the definition, it is not easy to get an overview of all relevant nudging studies and compare and evaluate different nudges. Put simply, I am not optimistic when it comes to the future of nudging as a research field.

It is difficult not to think about nudging when reading the brief paper by Gigerenzer (1998) on one-word explanations as surrogates for theories (written several years before researchers talked about nudging): “The first species of theory surrogate is the one-word explanation. Such a word is a noun, broad in its meaning and chosen to relate to the phenomenon. At the same time, it specifies no underlying mechanism or theoretical structure. The one-word explanation is a label with the virtue of a Rorschach inkblot: a researcher can read into it whatever he or she wishes to see.”

This pretty much sums up the cumulative science on nudging. Nudging is a Rorschach inkblot. There are no underlying mechanism or theoretical structure to the concept that enable us to make any theoretical progress. On the contrary, researchers can easily integrate their favourite theories and mechanisms into the nudging agenda (as long as the intervention is not imposing significant material incentives). Accordingly, we might be better off not using the concept of nudging and instead be a lot more explicit about the concepts, mechanisms and constructs we are interested in.

My prediction is that a lot of progress within behavioral economics over the last few years will be seen in obtaining more parsimony and in better understanding the mechanisms we want to study. For example, in a recent study, Oeberst and Imhoff (2023) demonstrate how confirmation bias coupled with a handful of fundamental beliefs can explain an array of different cognitive biases (or, as Jon Ronson have formulated it, “Ever since I first learned about confirmation bias I’ve been seeing it everywhere.”). Nudging, on the other hand, invites all theories, mechanisms, and biases into the domain, making it next to impossible to see how scientific progress can be made.

4. No clear comparison

How do we evaluate the impact of a nudge? Is it sufficient to compare the impact of a nudge to no intervention? Specifically, what are the opportunity costs to nudging? There is strong evidence for opportunity cost neglect in the domain of public policy (cf. Persson and Tinghög 2020), and it is interesting how little attention is being devoted to the opportunity costs of nudging.

Benartzi et al. (2017), for example, argue that while nudging is a valuable approach, more calculations are needed to determine the relative effectiveness of nudging. In the paper, the authors compare different types of interventions and find, among other things, that a social-norms nudge is more effective at energy conservation than a health-linked usage information nudge. However, interestingly, they also find that electricity bill discounts and incentives and education are more effective than a health-linked usage information nudge. Furthermore, there is some discussion about whether “social norm nudges” are in fact nudges (see, e.g., Mols et al. 2015).

In a recent study on climate change mitigation behaviours, Bergquist et al. (2023) conduct a second-order meta-analysis and find that social comparison and financial approaches were the most effective tools (and information and feedback were the least effective). In other words, we cannot simply assume that nudges work better than financial approaches (in particular with strong economic incentives). Nudging is often sold on the idea that we can alter people’s behaviour in predictable ways with small interventions, but there is little reason to expect for this to actually be the case.

This is not to say that we should not focus on nudging, but that we should aim to compare it to other non-nudging techniques. Nudges might be cheap (this is part of their appeal), but the development and implementation might not be worth the money (compared to the effectiveness of other interventions). Accordingly, we should always consider the opportunity costs of nudging.

5. No effect on big problems

Can nudging help us address the big problems we face in 2023? I am less convinced that small nudges can help us solve big problems. Or as Tom Goodwin formulated it more than ten years ago: “[Nudging is] not an effective strategy for bringing about the kind of behavioural changes required to solve society’s ‘big problems’ – problems around climate change and public health, for example.”

There are three particular issues with nudging and big problems. First, nudging is biased towards small interventions. It is relevant to consider how we can change human behaviour with as small interventions as possible (a basic principle of libertarian paternalism), but we might be better off focusing more on large interventions when addressing big problems. During the COVID-19 pandemic, several studies tried to demonstrate how nudging could make more people get vaccinated. My guess is that, at the end of the day, nudging had little to no impact on putting an end to the pandemic. Kantorowicz-Reznichenko et al. (2023), for example, found that nudges had no impact on vaccination intentions as there are broader societal dynamics at play that makes nudging less effective (such as belief in conspiracy theories and political ideology).

Second, nudging focuses primarily on interventions that can be examined in an experimental setting. This is what Gal and Rucker (2022) call for an experimental validation bias: “the tendency to overvalue interventions that can be ‘validated’ by experiments. This bias results in interventions of limited ambition and scope, leading to an impoverished view of the relevance of behavioural science to the real world.” Of course, experimental validation is amazing, and in most cases of paramount importance, but I fully agree that we tend to overvalue such interventions within behavioural economics in general and nudging in particular when trying to address big problems such as climate change and pandemics.

Third, and related, nudging is often focused on small problems that can be addressed here and now. Accordingly, the time frame is often short when we evaluate a nudge, and rarely – if ever – do we look at the impact of a nudge over several weeks. For big problems, we should often look at solutions that will take many years. Lyon et al. (2022), for example, argue that climate change action must look beyond 2100! Noteworthy, this is not only a critique of nudging, but the short time frame is particularly relevant when we talk about nudging. One might even expect that for some nudges the short-term effects overestimate their long-term benefits.

We know that nudges have small effects on small problems, and as such, it should be no surprise that nudges do not have large effects on big problems.

6. Focus on individual solutions

Nudging focuses too much on individual solutions. This is the key argument presented in a paper by Chater and Loewenstein (2022). Specifically, they introduce a distinction between two types of interventions (frames): the i-frame and the s-frame. The i-frame is an intervention that seeks to change individual behaviour. The s-frame is an intervention that seeks to change the system in which they operate.

Nudging is interested in changing people’s behaviour (in predictable ways) directly, and not to change the system in which people operate and make decisions (i.e., the s-frame). The problem with nudging is that it primarily focuses on individual solutions (i.e., the i-frame). When problems are not individual but systemic, nudges can work as a harmful diversion. In the paper, Chater and Loewenstein (2022) present various different i-frame and s-frame interventions across different policy issues. For climate change, for example, one potential i-frame intervention is a carbon footprint calculator, whereas a potential s-frame intervention is carbon pricing.

There are at least two arguments in favour of nudging despite the focus on i-frames. First, one can say that it is not a trade-off between the i-frame and the s-frame, but that they each complement each other. For example, a carbon footprint calculator might make people more likely to care about climate change and thereby support changes in carbon pricing. Second, i-frame interventions can be used to nudge people in power (e.g., politicians) to pursue s-frame interventions (what we can call ‘meta-nudging’, cf. Dimant and Shalvi 2022).

However, despite these arguments, there is in my view no doubt that nudging is heavily biased towards individual solutions (and thereby framing problems as individual problems), rather than focusing on systemic problems and solutions. As I outline below, this is convenient for policy-makers, businesses and other actors that want to avoid responsibility for their actions (and lack of action) and put the responsibility on individuals.

7. Bias towards biases

People working with nudging love to talk about cognitive biases. Gigerenzer (2018) argues that there is a ‘bias bias’, i.e., a tendency to spot biases even when there are none. Most recently, Lionel Page has argued that we have reached the point of diminishing returns in the quest of identifying cognitive biases within behavioural economics. Accordingly, identifying yet another cognitive bias might even bias how we think about human cognition.

In the study of nudges, we tend to rely on methods that make it more likely to confirm the presence of cognitive biases. Lejarraga and Hertwig (2021), for example, outline how the heuristics-and-biases research program, initiated by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, that also underpins a lot of the literature on nudging, resulted in specific conclusions about human cognition. They argue that the heuristics-and-biases research relied primarily on described scenarios rather than actual learning and experiences. In brief, they conclude that “the focus on description at the expense of learning has profoundly shaped the influential view of the error-proneness of human cognition”.

The problem is that cognitive biases cannot account for many of the significant problems we see today, e.g., the lack of upward economic mobility (Ruggeri et al. 2023). When we aim to address problems primarily, though not exclusively, via cognitive biases, we only get a limited sense of the problem and potential solutions.

In addition, researchers interested in nudging are just as prone to confirmation bias as everybody else, i.e., we seek confirming evidence (enumerative induction rather than eliminative induction), cf. Wason (1960) and Jonas et al. (2001). We rarely ask what evidence will prove us wrong, and this is a basic feature of our reasoning. Or as Julia Galef describes it in The Scout Mindset: “Motivated reasoning is so fundamental to the way our minds work that it’s almost strange to have a special name for it; perhaps it should just be called reasoning.”

Last, just because people who nudge are aware of specific cognitive biases, it is not guaranteed that they will not be biased in how they design nudges. Strulov-Shlain (2022), for example, shows that retailers respond to left-digit bias by using 99-ending prices, but how they respond is more in line with heuristics than with optimization (meaning that retailers forgo 1–4% of potential gross profits).

In sum, a bias towards biases might leave us with a biased understanding of the relevance and importance of nudging.

8. Nudging as a non-intervention tool

While nudging is now an important intervention tool, it can also be seen as a non-intervention tool. In fact, one reason companies endorse nudging is to show that they do something while do very little, primarily to avoid regulation. For example, it was British Petroleum that introduced the term ‘carbon footprint’ to put attention on individual responsibility for climate chance. We have already talked about this change in focus from s-frame interventions to i-frame interventions, and if you want to change the framing of a problem from a systemic to an individual issue, nudging is the ideal tool.

Hagmann et al. (2023) have demonstrated the implications of focusing on individual behaviour empirically. They find that when people learn about policies targeting individual behaviour, they are more likely to hold individuals rather than organizational actors responsible for solving problems such as climate change, retirement savings, and public health.

Similarly, Gigerenzer (2015) outlines how the scientific evidence for nudging “focus the blame on individuals’ minds rather than on external causes, such as industries that spend billions to nudge people into unhealthy behavior”. Again, if a company or politician prefer not to change status quo, nudging might be a sensible solution.

There are several specific reasons why politicians might want to nudge despite such interventions having little to no impact. Most relevant, there is an action bias in politics, meaning that actions are evaluated more positively than inactions regardless of the outcome (Olsen 2017). Egan (2014) also shows that the public, when faced with a new problem, prefers the government to do something about the problem. If that “something” can be cheap and easy, like a nudge, everything is fine.

This is also called a placebo policy, as defined by McConnell (2020): “a policy driven to some degree by an attempt by policy makers to demonstrate that they are ‘doing something’ to tackle a policy problem, rather than addressing deeper causal factors of the policy problem.” My concern is that a lot of nudges today are better understood as placebo policies than actual policies.

9. Buzzword for business

Nudging is whether you like it or not a buzzword. Simply by calling something a nudge, it will get more attention. It sounds better to call an intervention a ‘nudge’ than a ‘leaflet’. The concept of nudging is overrated by now and we have been way too positive in how we frame and sell nudging as a solution. A recent study by Trummers (2023), for example, showed that the media has been mostly positive in their coverage of nudging.

Many nudges have been developed to show how colourful and attention-grabbing interventions can nudge people. However, there is evidence that such interventions might not be useful and can even make official communication be interpreted as less credible and important. Linos et al. (2023) have demonstrated this effect (an effect they call the ‘formality effect’, where people interpret a formal letter as more competent and trustworthy). In other words, just because something is new and exciting, we should not expect for it to be effective.

Last, part of what makes nudging attractive is the fact that we work with more ‘advanced’ models of human behaviour. However, there is evidence that simple models predict behaviour at least as well as behavioural scientists, cf. Bowen (2022). Despite being a buzzword, we should not necessarily see nudging as an improvement to simpler models of human behaviour.

10. Ethical concerns

Nudging is the ‘have your cake and eat it too’ of behavioural economics. You can obtain your policy goals without having to limit the freedom of ordinary people. This is one of the core arguments in favour of nudging, and a lot of work has been done over the years on the ethics of libertarian paternalism and questions related to whether people want to be nudged or not.

However, a lot of the ethical concerns related to nudging, and in particular reasons not to be concerned, are misguided, or at least not the most important concerns related to nudging. That is, I believe a fundamental aspect of any policy-making should deal with democratic accountability and political trust. I am less concerned about whether it is ethical to nudge a single person (or whether that person wants to be nudged or not). What I am worried about are the feedback effects of nudging. How do people see policy-making and democracy in the wake of nudging? I am not convinced that nudges will make people more likely to have trust in politicians and the democratic procedures.

We know that political trust matter for support for future-oriented policies such as reducing global warming and public debt (Fairbrother et al. 2021). Will the focus on nudging increase public trust in policy-makers? My concern is that, if anything, it will decrease public trust.

In sum, while ethical discussions related to libertarian paternalism and the like are important, additional attention is needed on ethical issues related to the mix of concerns raised above. We can call these issues the second-order ethical issues related to nudging. That is, discussions not related to whether it is OK or not to nudge in the first place, but the feedback effects and implications of nudging beyond the specific individuals being nudged.

Nudging is here to stay. However, and maybe exactly for this reason, it is important to critically discuss the issues with and limitations of nudging. Again, do not see the above as reasons to disregard nudging, but as an overview of my main concerns related to nudging today.