I do not read a lot of news in a traditional sense. I do not open up the daily newspaper. I rely on my curated Twitter feed and several blogs to keep myself posted on what goes on, up and down in the world. For that reason, I might not be the target audience for the most recent book by Rolf Dobelli, Stop Reading the News: A Manifesto for a Happier, Calmer and Wiser Life. However, I always appreciate a good book that can confirm my habits (almost as much as a good book that can challenge my habits).

I am familiar with some of the work by Rolf Dobelli. I have read his 2010 eassy Avoid News: Towards a Healthy News Diet (the book in question is pretty much the book-length version of this essay) and his book The Art of Thinking Clearly (where parts of it was plagiarised from Nassim Nicholas Taleb).

The radical proposition of Stop Reading the News is that you should … stop reading the news. Here is what the author has to say: “When I ask you to give up the news, I can do so with a clear conscience. It will make your life better. And trust me: you’re not missing anything important.” There are two immediate issues with this. First, how can you generalise from the single case of the author to all readers (and non-readers?) of the book? Second, how can you conclude that you are not missing anything important when you are not following the news? Both of these issues are – in different ways – a missing data problem.

However, the main problem I have with the book is not what it offers, but that it does bring any observable evidence or even convincing arguments to the table. Upon reading the book, there is no reason to conclude that you should stop reading the news. Most of the evidence in the book is, when not absent, anecdotal. Instead of actual evidence, the author relies on repeating the same points again and again.

Interestingly, the author is not making the argument that you should read less news, but that you should read no news. No newspaper subscriptions, no TV news, no radio bulletins, no online news, etc. Why? Because news “is to the mind what sugar is to the body: appetising, easily digestible and extremely damaging.” What is the evidence? None. There is no evidence whatsoever that news is “extremely damaging” to the mind.

I am also not convinced that sugar is the best metaphor. The author sounds a lot more like an alcoholic talking about the problems with drinking even one beer. Here is one example from the book: “Hello, my name is Rolf, and I’m a news-aholic.’ If there were self-help groups for news junkies like there are for alcoholics, that’s how I would have introduced myself to the group, hoping they would understand.” And here is another example: “In fact, the news is every bit as dangerous as alcohol. Even more so, actually, because the obstacles to boozing are much harder to overcome.” And here is a third example: “We can gobble down as many articles as we like, but we will never be doing more than gorging on sweets. As with sugar, alcohol, fast food and smoking, the side effects only become apparent later.” And here is a fourth example: “Imagine if cigarettes, alcohol and cocaine were not only free but actually offered to you on all sides, round the clock, by invisible hands. There’s no doubt most of us would be hooked. This is precisely what’s happening with the news today.”

Again, all of these enormous assertions are unbacked by any evidence. There is no evidence that news is as dangerous as alcohol, let alone more dangerous. There is definitely no evidence for the long-term negative effects of news consumption. I wish I could say that the above examples are not representative for the book at large. Alas, this is not the case. The book is full of unsubstantiated empirical claims.

Take this counterintuitive statement: “The relationship between relevance and media attention seems inverse: the greater the fanfare in the news, the smaller the relevance of the event.” Again, no empirical evidence. I believe that this statement is only counterintuitive because it is simply not true. Most events are not reported in the news, and that is not because those events are the most relevant!

Or take this claim: “The upshot is clear: consuming the news reduces your quality of life. You will be more stressed, more on edge, more susceptible to disease, and you’ll die earlier. That’s an especially sad piece of news – but one that does, at least, deserve your attention.” Here is some good news: There is no empirical evidence that you’ll die earlier from consuming news. And I see no reason why not consuming the news should make you live longer.

Here is another exaggerated and extreme claim: “If you consume the news, just be aware that you’re unintentionally supporting terrorism.” I get the argument the author is trying to make (terrorists benefit from attention), but there is no empirical evidence to even suggest that you are unintentionally (or intentionally) supporting terrorism just by consuming news.

I am not saying that you always need to cite empirical evidence, but the more extreme the claim, the more you should be able to support it. It is, for example, okay to be concerned about fake news, but not okay to conclude that the “the sheer volume of fake news has mushroomed”, if there is no evidence to support this (and if all relevant studies conclude that it is not the case, e.g., Grinberg et al. 2019 and Guess et al. 2019).

Even in the few instances where the author introduces actual research, we see significant problems. You will, for example, find claims related to ‘ego depletion’, i.e. “once your willpower is depleted, you don’t have any left over for the next challenge.” I guess the author did not read the news on the challenges with replicating this finding. Actually, the empirical evidence (and the lack hereof) offered throughout the book pretty much confirms that the author has not followed the news for at least ten years.

A conceptual problem I have with the book is that it is talking a lot about the news without really understanding what news is. Again, let us take one example: “News is the opposite of understanding the world. It suggests there are only events – events without context. Yet the opposite is true: nearly everything that happens in the world is complex. Implying these events are singular phenomena is a lie – a lie promulgated by news producers because it tickles our palates. This is a disaster: consuming the news to ‘understand the world’ is worse than not consuming any news at all.”

If you understand news as the opposite of understanding the world, then it is easy to make a case against news. However, this is a straw man argument and not a true representation of what news actually is. News is not always or exclusively presenting events as singular phenomena, and I fail to see how you can conclude that there is no context offered in the news. A lot of good journalism is all about providing the context for current events. There is no reason to believe that consuming no news is better than consuming the news to understand the world.

I have a lot of problems with the book and I am for the most part holding the author responsible for those problems. However, I can’t stop to think that the author is unlucky in terms of the timing of the book. The book is published in 2020 just prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. This is an event where it is crucial to follow the news for reliable information about what to do (and not to do). What should be my source of information during a pandemic if not the news?

The author speculates about what exactly will happen if something truly significant happens: “If something truly significant happens, you’ll find out soon enough – from the specialised press, from your friends, your family, or someone you’re chatting to. When you meet up with friends, ask them if anything important has happened in the world. The question is an ideal conversation-starter. The usual answer? ‘Not really, no.”

Here is the problem. In the midst of a pandemic, I do not want to rely on family and friends, or even the specialised press (whatever that is), to keep me posted on what happens. I want reliable information that has not been interpreted and shaped by friends and family. And I especially would appreciate if most people would get their news from trusted media outlets and not from whatever their friends believe.

The author is trying to make this sound like a good thing: “Big news will inevitably leak out and find you. If you hear it from family, friends and colleagues you’ll even have the added benefit of meta-information”. Meta-information!? This is a bug, not a feature. I know I shouldn’t be too critical towards the author here. Again, he got unlucky with the timing of the book, but it is hilarious to read about the irrelevance of news in a time where we need reliable news more than ever.

The COVID-19 pandemic is actually a good case in point to show that news is not only about “singular phenomena” or events without context. The news has demonstrated how complex it is to live in a pandemic, how much uncertainty we face, etc. This is not to say that all journalism has been good during the pandemic (there has been a lot of low-quality journalism!), but I fail to see how not consuming the news is better than consuming the news if you are to understand the world, especially in – but not limited to – a global pandemic.

A statistic that is mentioned multiple times in the book is 90 minutes per day. This is used to say that people consume ninety minutes of news per day. Here is the empirical evidence for this claim: “The sum total is the entirety of the time you spend actually consuming the news. The Pew Research Center – an American think tank that canvasses public opinion – estimates this figure to be between fifty-eight and ninety-six minutes per day.”

Between 58 and 96 minutes? How convenient to go with 90 minutes, especially if you want to conclude that “If you stop reading the news, you’ll have reclaimed a whole month out of the year.” What? Do you spend one month every year reading news? If you spend 1/12 of your day consuming news, that is two hours – not one and a half! You can do a few different calculations but none that are favourable to reclaiming a whole month out of the year.

And here is another example of the ninety minutes: “If the first thirty days are already behind you – if you started before you picked up this book, for instance – then congratulations! You’ve reclaimed ninety minutes out of your day. That adds up to one workday per week. Even at a conservative estimate, that’s more than a month per year. Your year now has twelve months in it, not eleven, like it did before.”

Even at a conservative estimate? 90 minutes per day is not a conservative estimate of 120 minutes per day. From my calculations it can, at best and if we assume the numbers are correct, be 22 days a year. But maybe most people do consume news for a few hours a day?

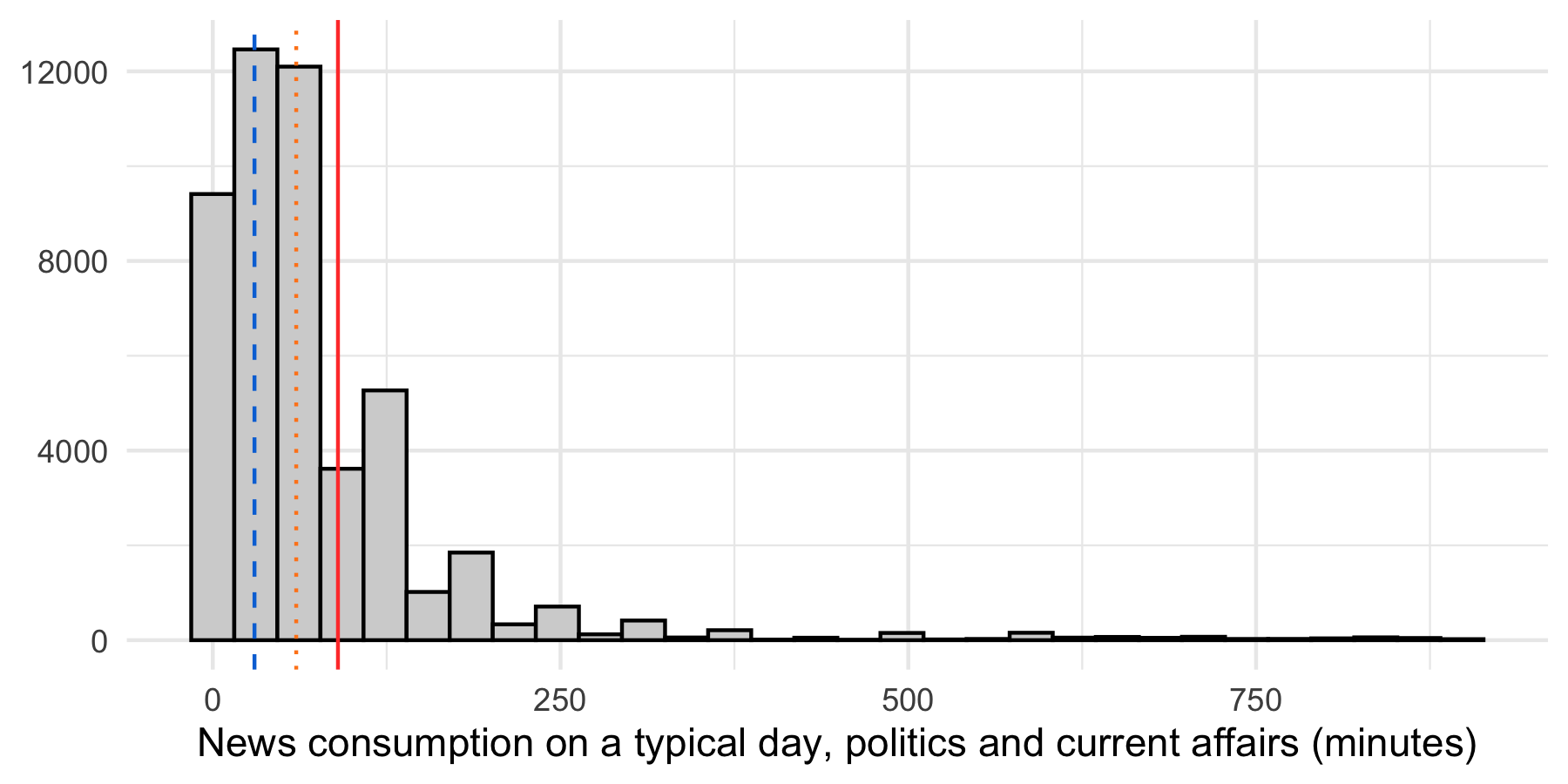

I decided to take a quick look at Round 9 from European Social Survey, where the respondents are asked to answer the question “On a typical day, about how much time do you spend watching, reading or listening to news about politics and current affairs?”. This is self-reported data and by no means perfect data (people might, for example, watch news that are not related to current affairs). The figure below shows the distribution of all answers.

The blue dashed line indicates 30 minutes, the orange dotted line indicates 60 minutes, and the red line indicates 90 minutes. A lot of people consume news for around 30 to 60 minutes a day. The majority of the respondents report consuming less than 90 minutes a day (the median response is 60 minutes on a typical day). In the figure, I have excluded respondents above the 99th percentile (some respondents answered 1440 minutes a day, i.e., 24 hours).

If we assume for a second that the data from the European Social Survey is reliable, I do not see any reasons for concerns. An hour a day to keep yourself up-to-date on politics and current affairs is fine. Of course, some people might spend a lot of time consuming news, but it looks like a minority.

I will also contest that you can simply replace the time you consume news with other activities. If you work for four hours but spend half an hour reading the news, maybe you would not work as hard if you had to work for three and a half hours straight? And maybe other activities would not give you the same feeling as having a break?

There are good reasons to think about these counterfactual scenarios as the assumption in the book is that we can simply replace news with, say, reading a book a week: “Try to read a book a week. If after twenty pages it hasn’t expanded or altered your world view, or otherwise managed to capture your attention, put it aside. If, on the other hand, you find a book that tells you something new on every other page, read it cover to cover. Then read it again, straight away.” I don’t even know where to begin with this proposition. First, a book is not necessarily bad because it hasn’t captured your attention within the first twenty pages. Second, it is a weird recommendation to read all books twice. There is no way whatsoever that I am going to read this book twice. I even regret having read it once. (Or maybe I should have stopped reading the book after the first twenty pages!?)

The book is also full of hypothetical examples that I do not find convincing at any level. Take this example:

Let’s take the following event: a car drives over a bridge and the bridge collapses. What does the news media focus on? The car. The person in the car. Where they came from. Where they were going. How they felt during the accident (assuming they survived it). What kind of person they are (or were, before the accident). Of course, what happened to this person is tragic, but to us – given that we don’t know them – is it relevant? Not remotely. What’s relevant to us is the bridge! The structural stability of the bridge. Whether there are other bridges constructed in the same way and from the same materials, and if so, where those bridges are. That’s what actually matters – so that no one else gets injured. Not the car, or its driver. Any car could have caused the bridge to collapse. Perhaps even a strong wind or a dog trotting over it could have been enough. So why does the news media report on the crumpled car? Because it looks so marvellously horrible; because they can connect the story to a person – and because this story is cheap to produce.

Do we really believe that the media would not care about the structural stability of the bridge? And that no journalist would be interested in finding out whether there are other bridges with similar problems? If anything, I find such hypothetical examples to show more about the authors shortcomings than modern journalism. This is not to say that specific media outlets would not pay disproportionate attention to the car and the driver in their coverage, but the news media would definitely not only focus on the car and the driver.

Based on all the arguments presented in the book, the author concludes: “By now you’ll have realised that there’s only one solution: disconnect completely from the news.” No, I have not realised that the only solution is to disconnect completely from the news. And I feel bad if any reader of the book will be convinced by the arguments presented in the book and give up on the news.

This is not to say that we should not reflect upon what news we consume and how often we consume news. Actually, it is something I have put a lot of thought into. In our book on opinion polls, we discuss how it is not an easy task to define what news is and whether something is newsworthy: “In a hypothetical scenario where news was only published once a year, a new opinion poll would most likely be relevant on its own terms. However, with daily newspapers and shorter deadlines, a new poll is not necessarily interesting compared to all other polls that have been reported recently. This is a feature that makes it crucial to understand how opinion polls can differ in their newsworthiness according to how we define news.” (emphasis in original, p. 28f)

Whether something is relevant/newsworthy/important is conditional upon how we understand the frequency of news, and we now have the opportunity to check the news any second of the day. This can be a problem, and something that is worth taking serious, but “stop reading the news” is not a good advice across time, space and concepts. Some people might be better off from consuming less news, or different news, but I find it much more interesting to talk about the equilibrium that works best for most people.

I am simply not convinced that we would live in a better society if nobody consumed news. Take this example from the book: “How should we vote sensibly without the news? My recommendation: look first at what the candidates have achieved and only then at what they’ve promised. You may have to google this information, and perhaps you’ll end up on a news website. This doesn’t matter, however, so long as you and not the media or machines determine your path through the internet.” I do not find this realistic, and I am not convinced that democratic societies would be better if people determine their own “path through the internet”.

Why do I think some people will find the premise of the book appealing? Because there is a lot of virtue signaling in saying that you don’t follow the news. Just as there is in saying that you do not own a TV (I don’t own a TV) and do not eat sugar (I didn’t eat sugar in 2021). Not having to care about the news is a privilege (in the same way it is a huge privilege not having to care about politics), and the book is, if anything, only confirming that the author lives a privileged life where it is no longer important to keep track of what is happening in the world.

Consequently, I disagree wholeheartedly with the following conclusion: “For ten years I’ve consistently practised what I preach. The impact on my quality of life and decision-making has been remarkable. Try it. You’ve got nothing to lose. You have so much to gain.” I am convinced that this is what the author believes. However, I do believe you have a lot to lose if you stop reading the news. And most people, but not all, have very little to gain. If you do not read any news at all, I will even end my review with a simple recommendation. Start reading the news.