On 15 January 2020, the World Economic Forum released The Global Risks Report 2020. The report was published before we talked about COVID-19 which makes it an even more interesting read. There are a lot of risks in the world. Weapons of mass destruction, food crises, natural disasters, climate change, data fraud, unemployment, asset bubbles etc. All of these risks differ in likelihood and potential impact.

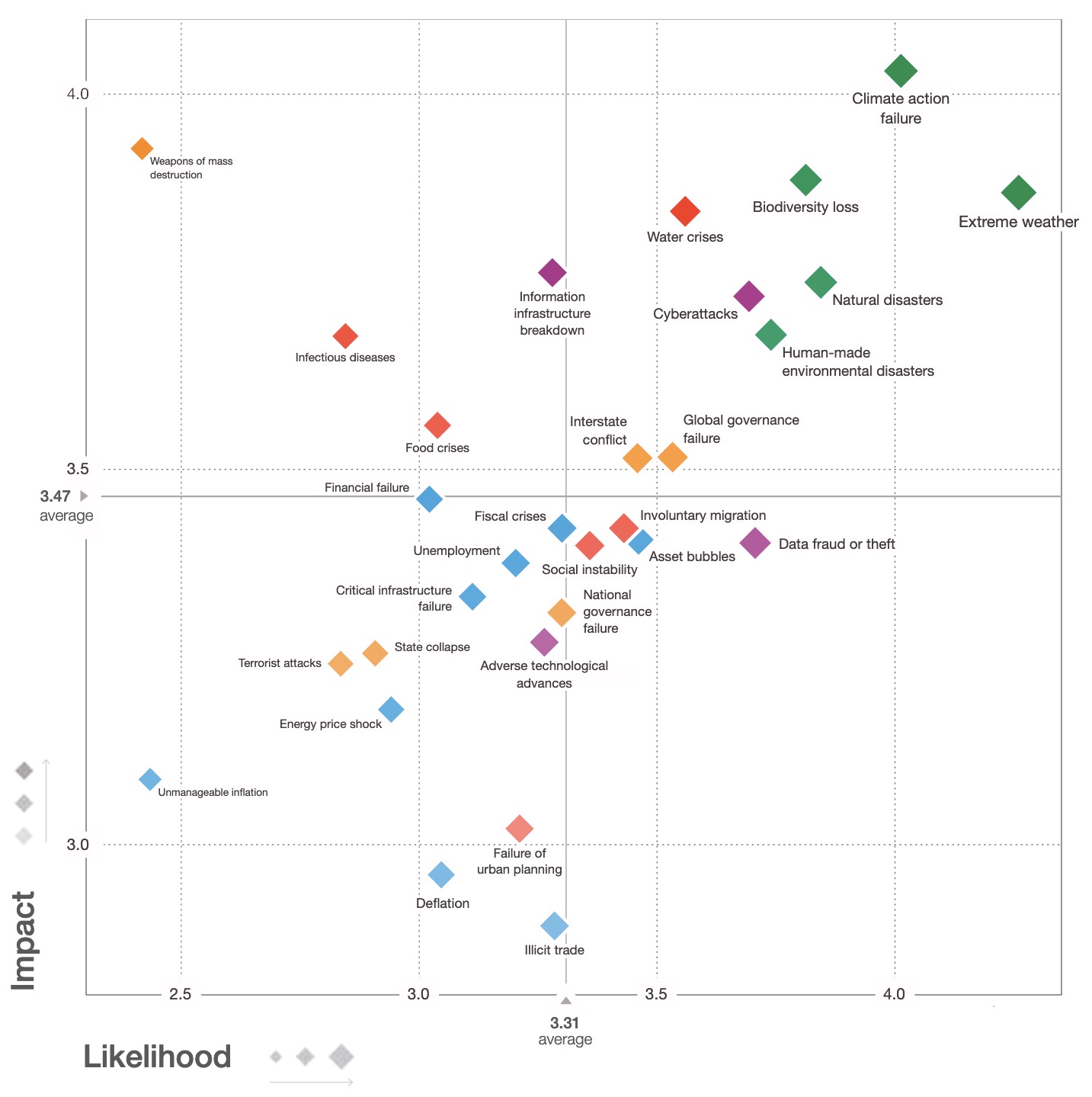

Here is the global risks landscape of 2020 according to the report:

We can see a few things here. First, there is a positive correlation between likelihood and impact (with weapons of mass destruction being an outlier). Second, most of the likely risks with a high impact are related to climate change. This is in line with what the economist Dina D. Pomeranz wrote on 31 December 2019: “The key issue that can endanger much of the progress the world have achieved in so many areas is climate change.” Third, infectious diseases is not that likely, and it is even more likely that we would face a critical infrastructure failure rather than infectious diseases.

Of course, what we know now is that infectious diseases would be a severe problem in 2020. However, on the risks landscape above it is below average in terms of likelihood. This might simply reflect that we are not good at considering the tail risk of contagious diseases. The global risk report is based upon survey data on risk perceptions and will, for that reason, not reflect the actual likelihood of an event happening.

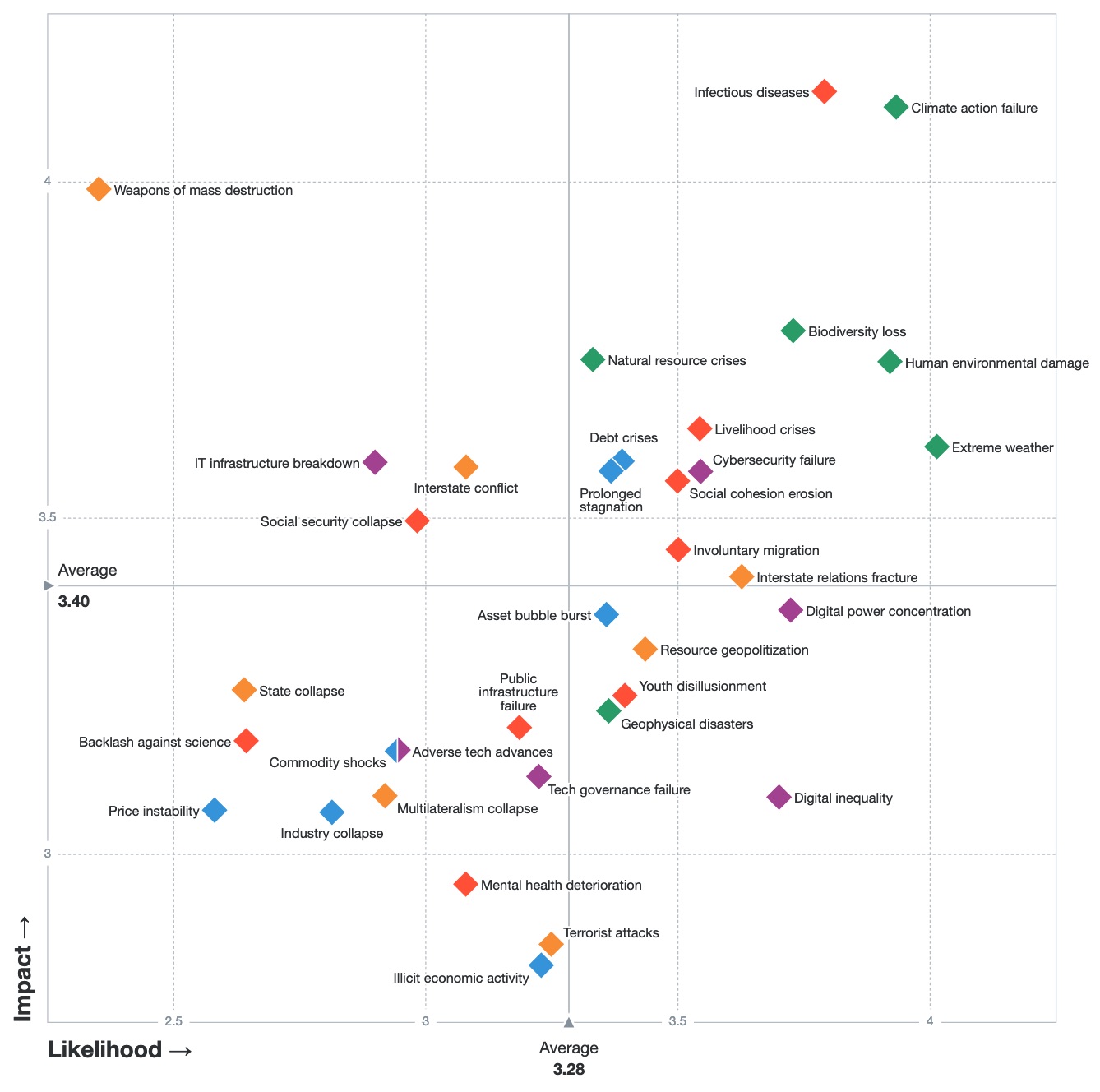

Tuesday, World Economic Forum launched their 2021 Global Risks Report. The top risks in terms of impact are now infectious diseases, climate action failure and weapons of mass destruction. Here is the new global risks landscape:

It is clear that the two risks with the biggest impact and likelihood are infectious diseases and climate action failure. But how should we think about these two risks? One possibility is to see them as unrelated. This would indicate that we should focus now on COVID-19 and then focus on climate change. However, I believe there are profound reasons for not see the risks as unrelated. On the contrary, these risks are correlated.

Noteworthy, there are important temporal differences between the two risks. While the climate crisis is happening right now, the key difference between the two crises is, in the words of Lidskog et al. (2020), the “urgency of action to counter the rapid spread of the pandemic as compared to the slow and meager action to mitigate longstanding, well-documented, and accelerating climate change”.

Risks are correlated and we cannot talk about infectious diseases as something that is completely unrelated to climate change. However, I believe that these risks will not be identical over time. Specifically, my sense is that the risks are negatively correlated in the shorter term but positively correlated in the longer term.

What we have primarily seen in the coverage of climate change in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic are stories about less pollution. We have all seen the various pictures of nature and subsequent “nature is healing” memes. COVID-19 led to a reduction in global CO2 emissions and air pollution, demonstrating certain short-term effects of the pandemic. Of course, this is not sustainable in the future and we cannot conclude that the solution to climate change is another pandemic.

On the contrary, climate change will make pandemics worse. Pandemics are related to the destruction of nature and will get worse because of climate change. Specifically, climate change is making it more likely that we will experience similar vira in the future, as described by Colin Carlson, an ecologist at Georgetown University, to Ed Yong: “the biggest factors behind spillovers are land-use change and climate change, both of which are hard to control. Our species has relentlessly expanded into previously wild spaces. Through intensive agriculture, habitat destruction, and rising temperatures, we have uprooted the planet’s animals, forcing them into new and narrower ranges that are on our own doorsteps. Humanity has squeezed the world’s wildlife in a crushing grip—and viruses have come bursting out.”

The key point is that we should treat the risk of pandemics and climate change within the same framework. Luckily, there has already been quite some attention to how the recovery from COVID-19 has to be green. In other words, it is not about returning to the world pre-COVID-19, but make a green recovery. The pandemic is a chance to do better for the climate and transition from a ‘brown’ to a ‘green’ economy over the next ten years. There are different ways to move forward and a strong green stimulus can meet global net-zero CO2 by 2050.

What we should care about is the long-term recovery and in particular the short-term costs to ensure long-term sustainability. One of the concerns is that climate change is already happening and COVID-19 is an inequality accelerator. For example, those who already experience the huge cost of climate change do more so during the pandemic. Again, the global risks related to pandemics and climate change are interconnected.

The good news is that, even in the midst of the pandemic, the public perceives climate change as a great threat – including in the United States and in Europe. The bad news is that there are important differences between a pandemic and climate change. Specifically, as Ramez Naam notes, “coronavirus is actually a much easier challenge for people to conceptualize”. Unsurprisingly, those who are more likely to be concerned about the pandemic and wear a mask will also be more likely to be concerned about climate change. For that reason, alas, I expect many of the challenges we have seen during the pandemic to still be relevant long after COVID-19.

We cannot self-isolate from the effects of climate change, but hopefully the experience with COVID-19 will have increased our understanding of global risks and enable scientists and politicians alike to address the risks of both infectious diseases and climate change.