Recently, there has been a lot of focus on the implications of using Facebook. One study, “The Facebook Experiment: Quitting Facebook Leads to Higher Levels of Well-Being“, argues that people who leave Facebook feel better with their lives. Matthew Yglesias talks about the study in this clip from Vox:

The study also got some attention back in 2016 when it was published (see e.g. The Guardian). This is not surprising as the study presents experimental evidence that people who are randomly assigned to not using Facebook felt better with their lives on a series of outcomes.

The only problem is that the study is fundamentally flawed.

The study finds that people who did not use Facebook for a week reported significantly higher levels of life satisfaction. The design relied on pre and post test measures from a control and treatment group, where the treatment group did not use Facebook for a week. The problem – and the reason we should not believe the results – is that people who took part in the study were aware of the purpose of the experiment and signed up with the aim of not using Facebook! In short, this will bias the results and thereby have implications for the inferences made in the study. Specifically, we are unable to conclude whether the differences between the treatment and the control group is due to an effect of quitting Facebook or is an artifactual effect.

First, when respondents are aware of the purpose of the study, we face serious challenges with experimenter demand effects. People assigned to the treatment group will know that they are expected to show positive reactions to the treatment. In other words, there might not be a causal effect of not being on Facebook for a week, but simply an effect induced by the design of the study.

An example of the information available to the respondents prior to the experiment can be found in the nation-wide coverage. The article (sorry – it’s in Danish) informs the reader that the researchers expect that using Facebook will have a negative impact on well-being.

Second, when people know what the experiment is about and sign up with the aim of not using Facebook, we should expect a serious attrition bias, i.e. that people who are not assigned to their preferred treatment will drop out of the experiment. In other words, attrition bias arises when the loss of respondents is systematically correlated with experimental conditions. This is also what we find in this case. People who got the information that they should continue to use Facebook dropped out of the study.

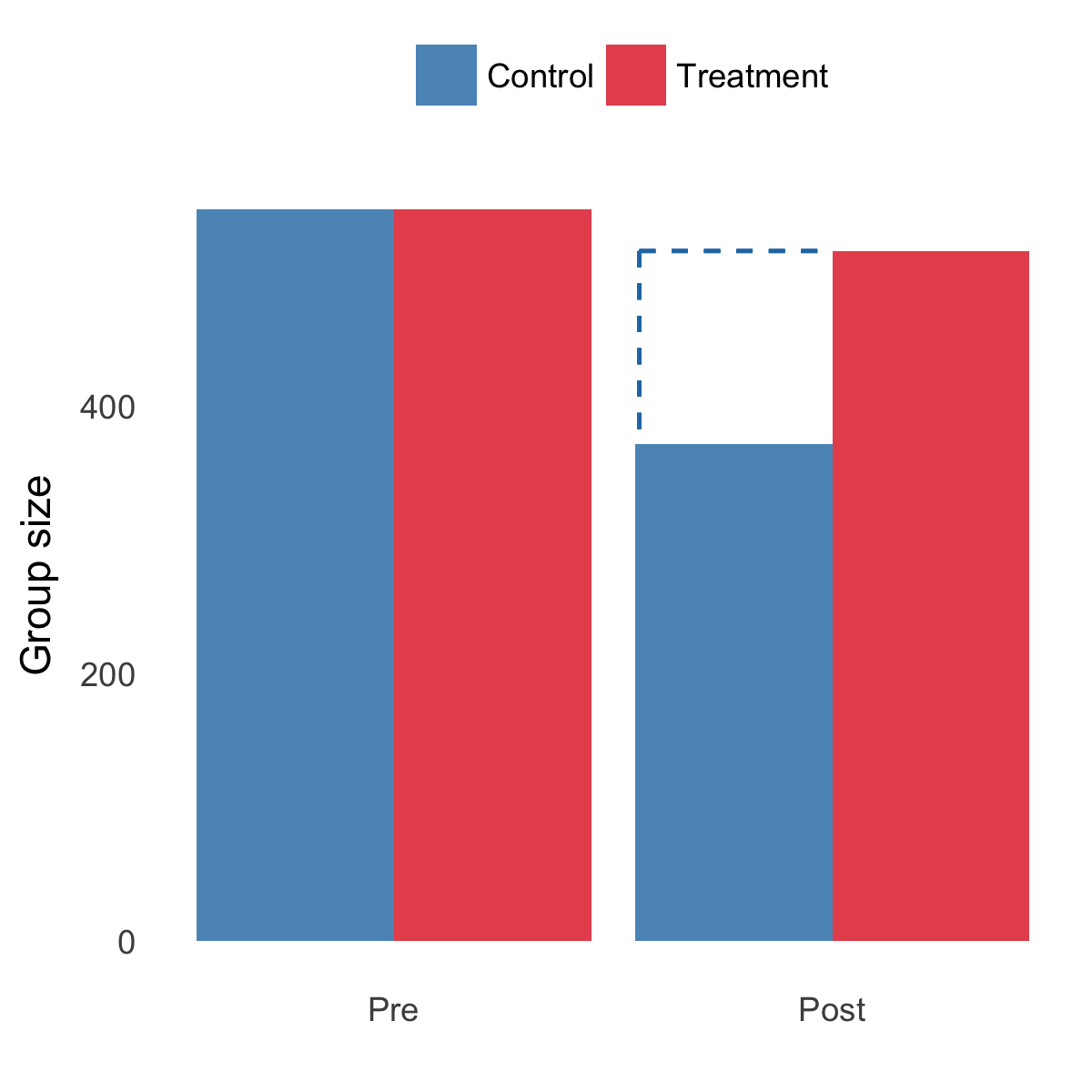

Figure 1 shows the number of subjects in each group before and after the randomisation in the Facebook experiment. In short, there was a nontrivial attrition bias, i.e. people assigned to the control group dropped out of the study.

Figure 1: Attrition across conditions

The dashed line indicates the attrition bias. We can see that the control group is substantially smaller than the treatment group.

Third, when people sign up to an experiment with a specific purpose (i.e. not using Facebook), they will be less likely to comply with their assigned treatment status. This is also what we see in the study. Specifically, as is described in the paper: “in the control group, the participants’ Facebook use declined during the experiment from a level of 1 hour daily use before the experiment to a level of 45 minutes of daily Facebook use during the week of the experiment.” (p. 663)

These issues are problematic and I see no reason to believe any of the effects reported in the paper. When people sign up to an experiment with a preference for not being on Facebook, we cannot draw inferences beyond this sample and say anything about whether people will be more or less happy by not using Facebook.