Gennem indlægget On the (Mis)Use of Regression Analysis: Country Music and Suicide, faldt jeg over Steven Stack og Jim Gundlachs paper (( Stack, S. & J. Gundlach (1992). “The Effect of Country Music on Suicide”, Social Forces 71(1): 211-218. )) fra 1992, der undersøger effekten af countrymusik på selvmord(!): »This article assesses the link between country music and metropolitan suicide rates. Country music is hypothesized to nurture a suicidal mood through its concerns with problems common in the suicidal population, such as marital discord, alcohol abuse, and alienation from work. The results of a multiple regression analysis of 49 metropolitan areas show that the greater the airtime devoted to country music, the greater the white suicide rate«.

Det er – som ovenstående link indikerer – ikke det bedste studie nogensinde foretaget i videnskabens historie, men det er jo også tyve år gammelt. Det er dog stadigvæk et godt eksempel på et studie med flere åbenlyse fejlkilder og problemer (spørgsmålet om den kausale sammenhæng, at slutte fejlagtigt fra gruppe-niveau til individ-niveau (“ecological fallacy“), måleproblemer m.v.). Flere af disse bliver belyst i et par replikationsstudier og kommentarer i tidsskriftet som det oprindelige studie blev publiceret i, men som (desværre) ikke bliver omtalt i indlægget.

Det første replikationsstudie (( Maguire, E. R. & J. B. Snipes (1994). “Reassessing the Link between Country Music and Suicide”, Social Forces 72(4): 1239-1243. )), foretaget af Maguire og Snipes i 1994, der ikke finder nogen signifikant korrelation mellem countrymusik og selvmordsrater, kommer med en sjov bemærkning i forhold til hvordan de måler våbentilgængeligheden: »They measured gun availability using “the number of retail outlets (per 100,000 population) listed under ‘guns’ or ‘firearms’ in the … yellow pages.” Although this is a poor measure of gun availability, to remain consistent, we too incorporated this measure.« (s. 1240).

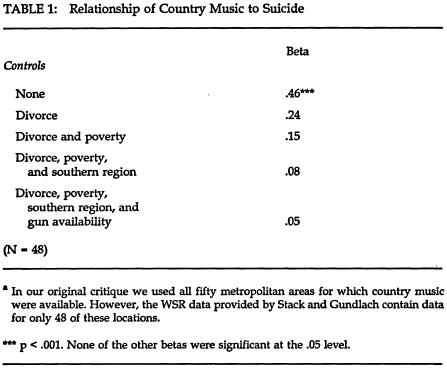

Dette afføder et paper (( Stack, S. & J. Gundlach (1994). “Country Music and Suicide: A Reply to Maguire and Snipes”, Social Forces 72(4): 1245-1248)) hvor Steven Stack og Jim Gundlachs kritiserer det pågældende studies måleproblemer på andre variable, og hvordan korrelationen er signifikant. Her svarer Maguire og Snipes igen (( Snipes, J. B. & E. R. Maguire (1995). “Country Music, Suicide, and Spuriousness”, Social Forces 74(1): 327-329. )), hvor det påvises, at sammenhængen er spuriøs: »Rather, as Table 1 shows, the relationship is spurious, attributable primarily to the effects of divorce and poverty, and to a lesser extent southernness and gun availability.«

I en kommentar (( Mauk, G. W., M. J. Taylor, K. R. White, T. S. Allen (1994). “Comments on Stack and Gundlach’s “The Effect of Country Music on Suicide:” An “Achy Breaky Heart” May Not Kill You”, Social Forces 72(4): 1249-1255 )) omhandlende, at An “Achy Breaky Heart” May Not Kill You, fremhæves nogle af de åbenlyse problemer med studiet der undersøger effekten af countrymusik på sandsynligheden for selvmord: »results of analyses of aggregate data on suicide are “suggestive but not conclusive” and that “researchers must make serious efforts to uncover the conditions under which inferences from aggregate to individual data are still permissible« (s. 1252). Ligeledes pointeres en lang række andre metodiske problemer, der er tekstbogseksempler på begrænsninger ved studiets resultater. For blot at nævne et par af dem relateret til deres data (s. 1252):

Lacking data on individual cases of suicide, one cannot know (1) whether whites who are depressed and suicidal tend to listen to country music or (2) whether whites tend to become depressed and suicidal as a result of listening to country music. Likewise, one cannot determine (1) whether whites who are divorced tend to listen to country music, (2) whether listening to country music tends to cause their noncountry music fan spouses to divorce them, or (3) whether country music makes romantic conflict and divorce seem more normal for those individuals who are contemplating suicide, thus increasing the likelihood that they will attempt suicide. Finally, it is unknown (1) whether whites who are suicidal are more likely to live in the southern region of the U.S. or (2) whether living in the southern region of the U.S. tends to cause whites to become depressed and suicidal.

Som det reagerer Stack og Gundlach (( Stack, S. & J. Gundlach (1995). “Country Music and Suicide – Individual, Indirect, and Interaction Effects: A Reply to Snipesand Maguire”, Social Forces 74(1): 331-335. )) på resultaterne ved at påvise simple korrelationer på individniveau mellem om man er fan af countrymusik og har været skilt eller separeret, og om man er fan af countrymusik og har et skydevåben, og konkluderer, at: »work is needed to explore the relationship between art and suicide, including country music.« (s. 335).

Studiet og de efterfølgende studier og kommentarer er gode eksempler på for det første hvor vigtige metodiske overvejelser (datavalg, operationaliseringer, indikatorer osv. osv.) såvel som replikationsstudier er, hvor mange faldgruber der er, og selvfølgelig den klassiske; korrelation ≠ kausalitet.